AUGEN AUF! 100 Jahre Leica Fotografie

Synopsis

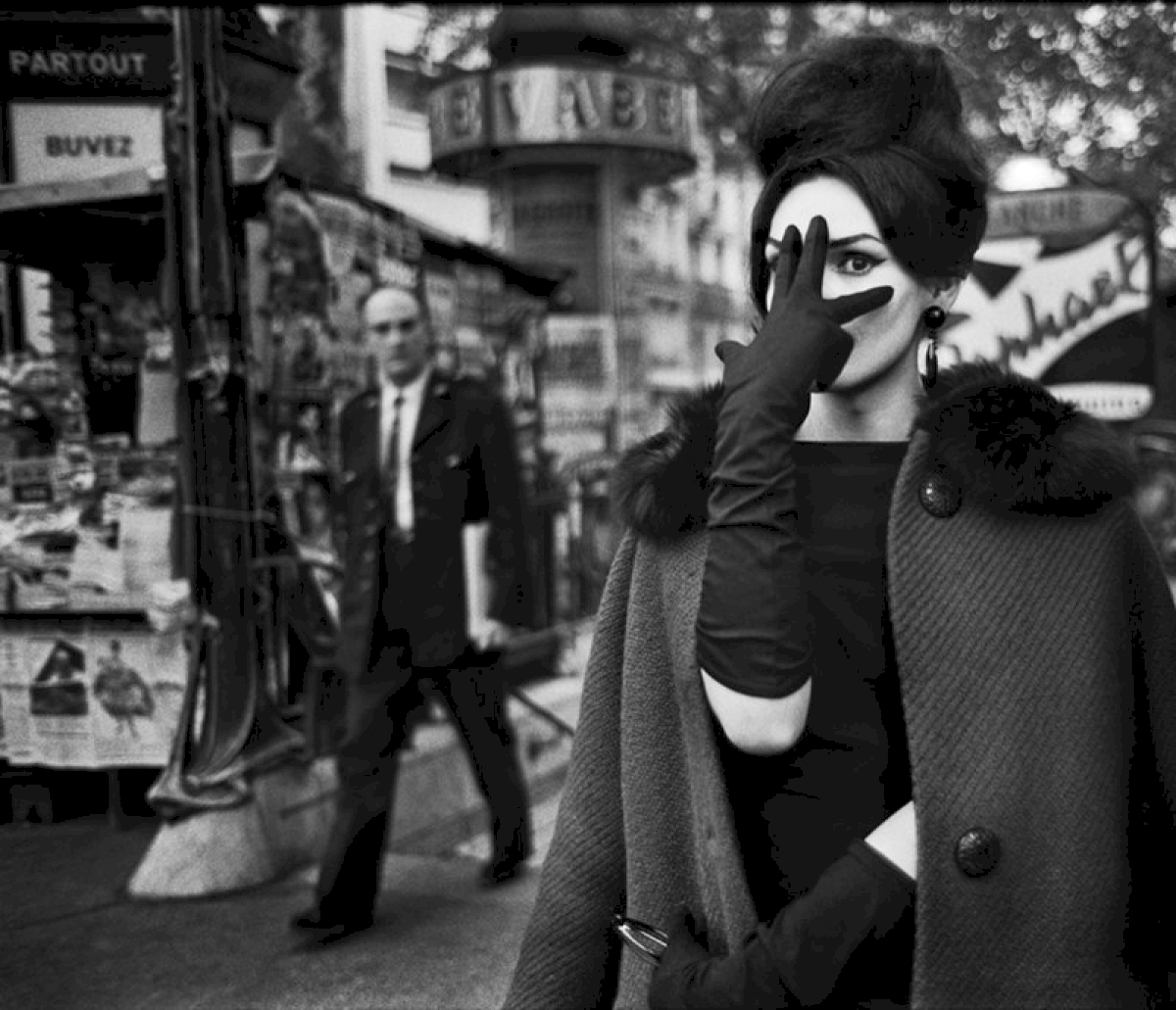

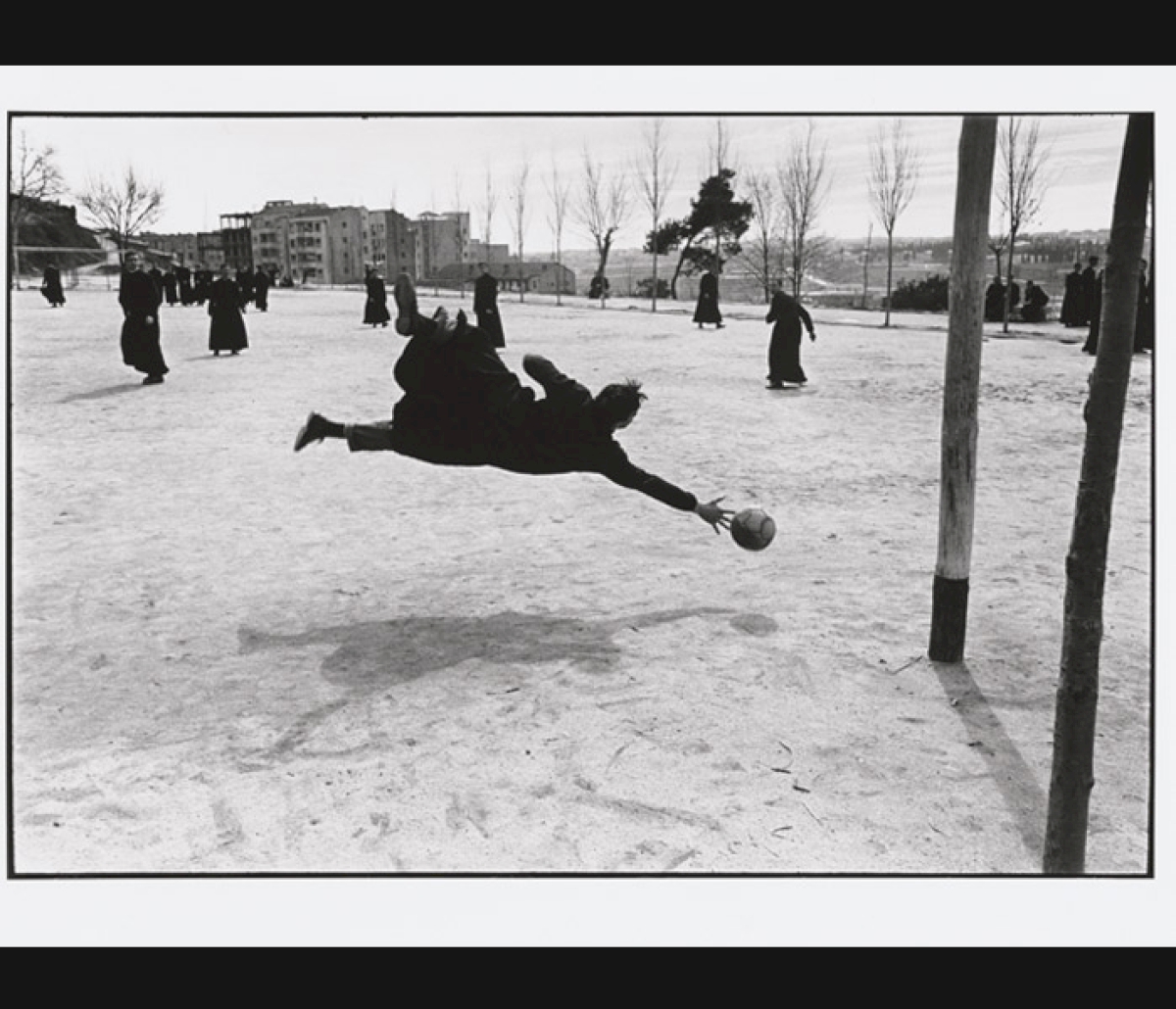

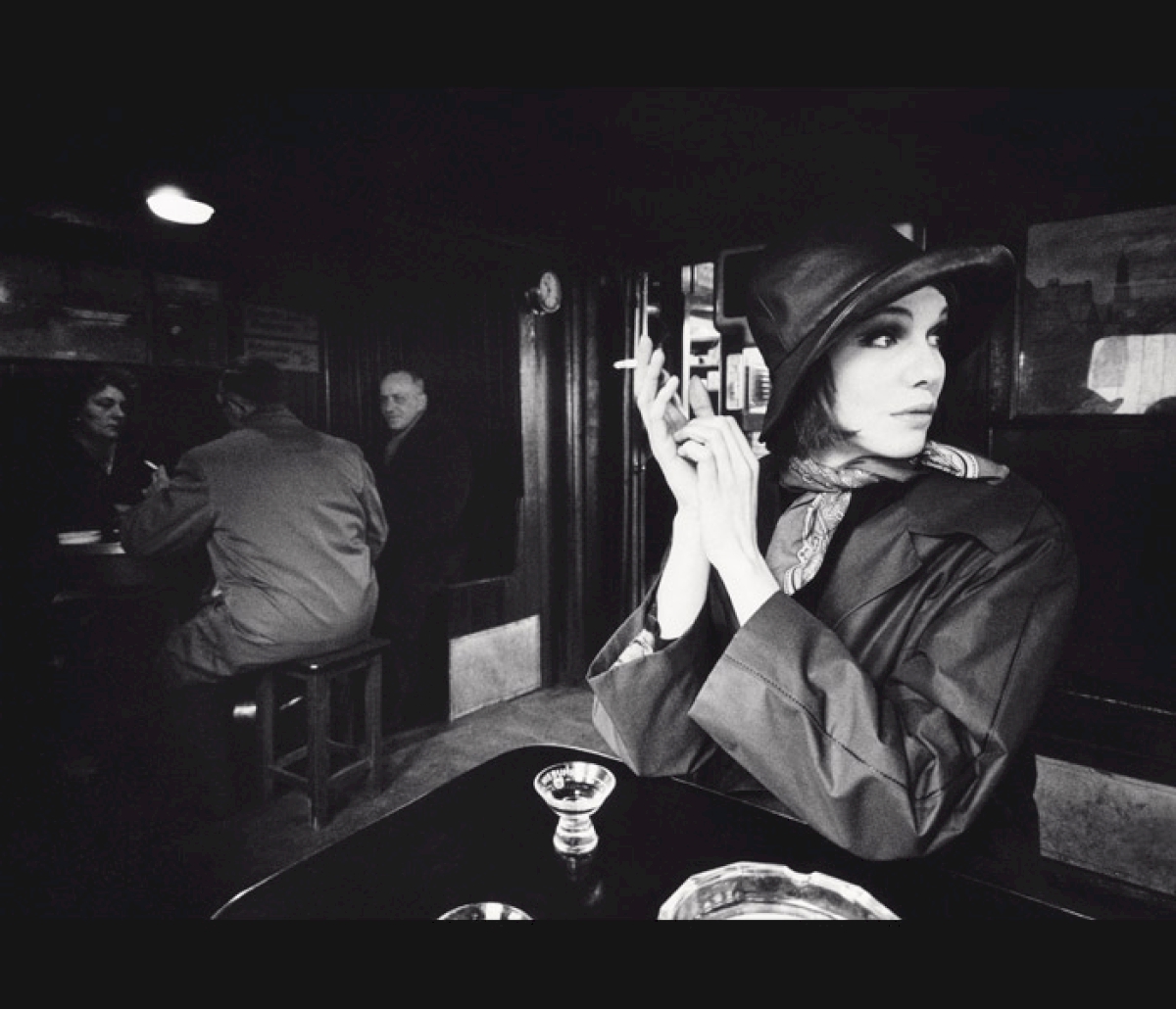

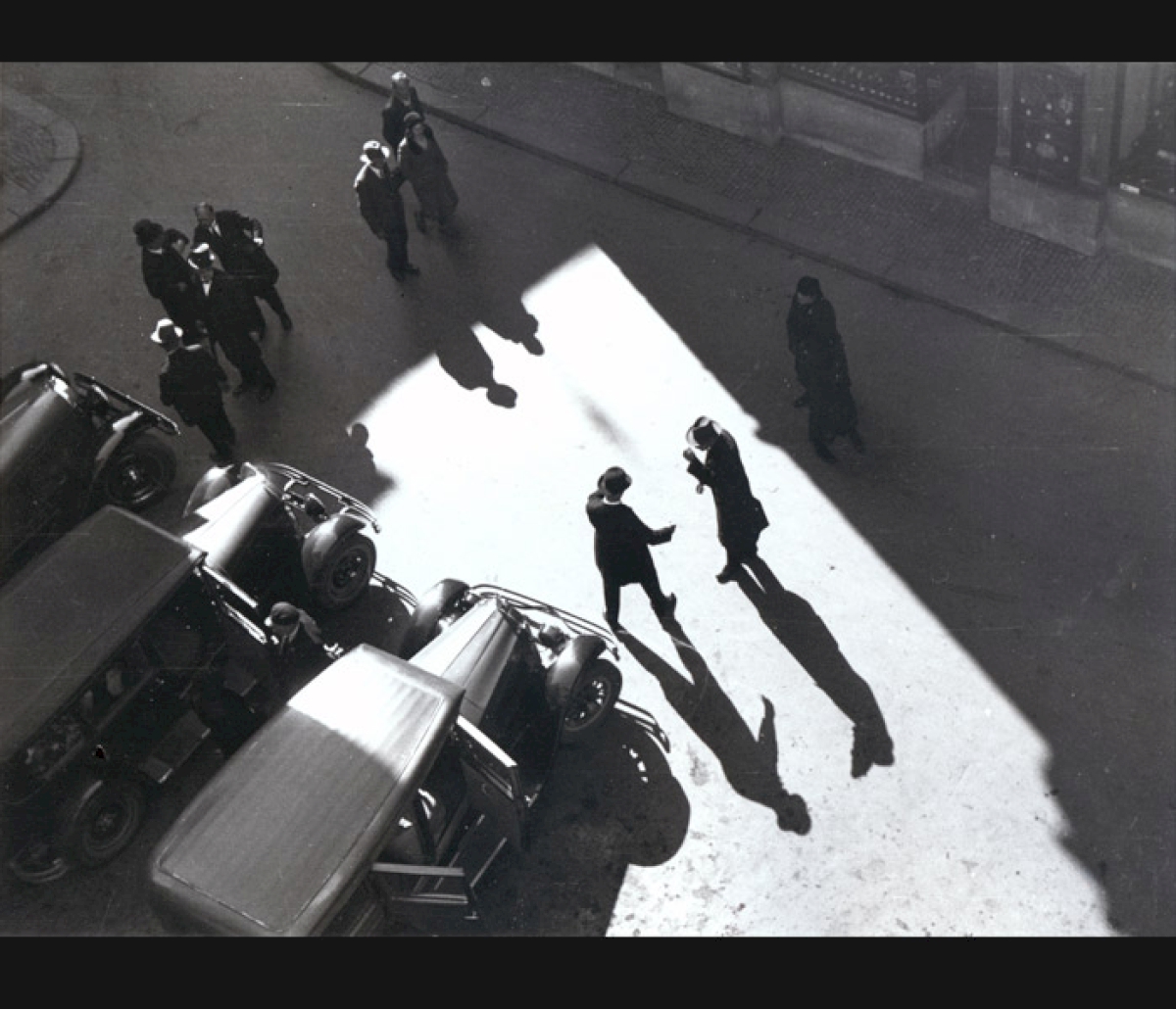

This camera changed the way we view the world. Forever. The falling soldier by Robert Capa, the puddle jumper by Henri Cartier-Bresson, the Times Square kiss by Alfred Eisenstaedt, Vietnamese children fleeing from a Napalm attack by Nick Út, the Soviet flag being raised above the Berlin Reichstag by Yevgeny Khaldei – all these famous photographs are Leica images, and they have etched themselves deeply into our collective memory. It was the Leica’s compactness and innovative technology that made photographs like these possible. The Leica’s predecessors were, for the most part, clumsy, heavy cameras. They were unwieldy and designed to yield one photograph per glass negative. It was nearly impossible to use them in a spontaneous manner. Before the advent of the Leica, taking photographs amounted to a staging of reality. The compact Leitz camera made spontaneity as well as candid street photography possible.

THE EXHIBITION

Dynamization, democratization, media revolution – great cultural changes are often attributed to technical innovations, and the introduction of the Leica 100 years ago is no exception.

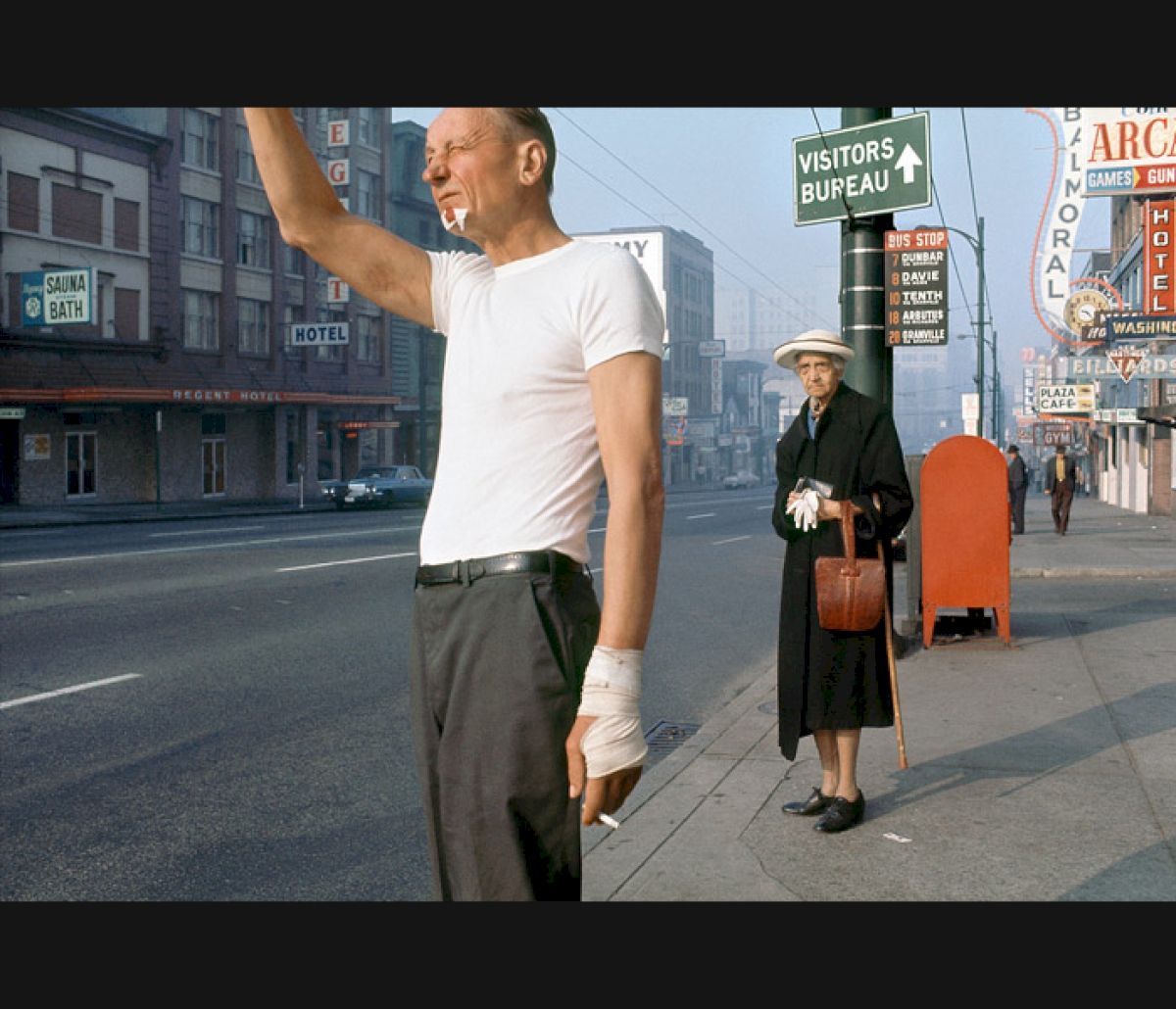

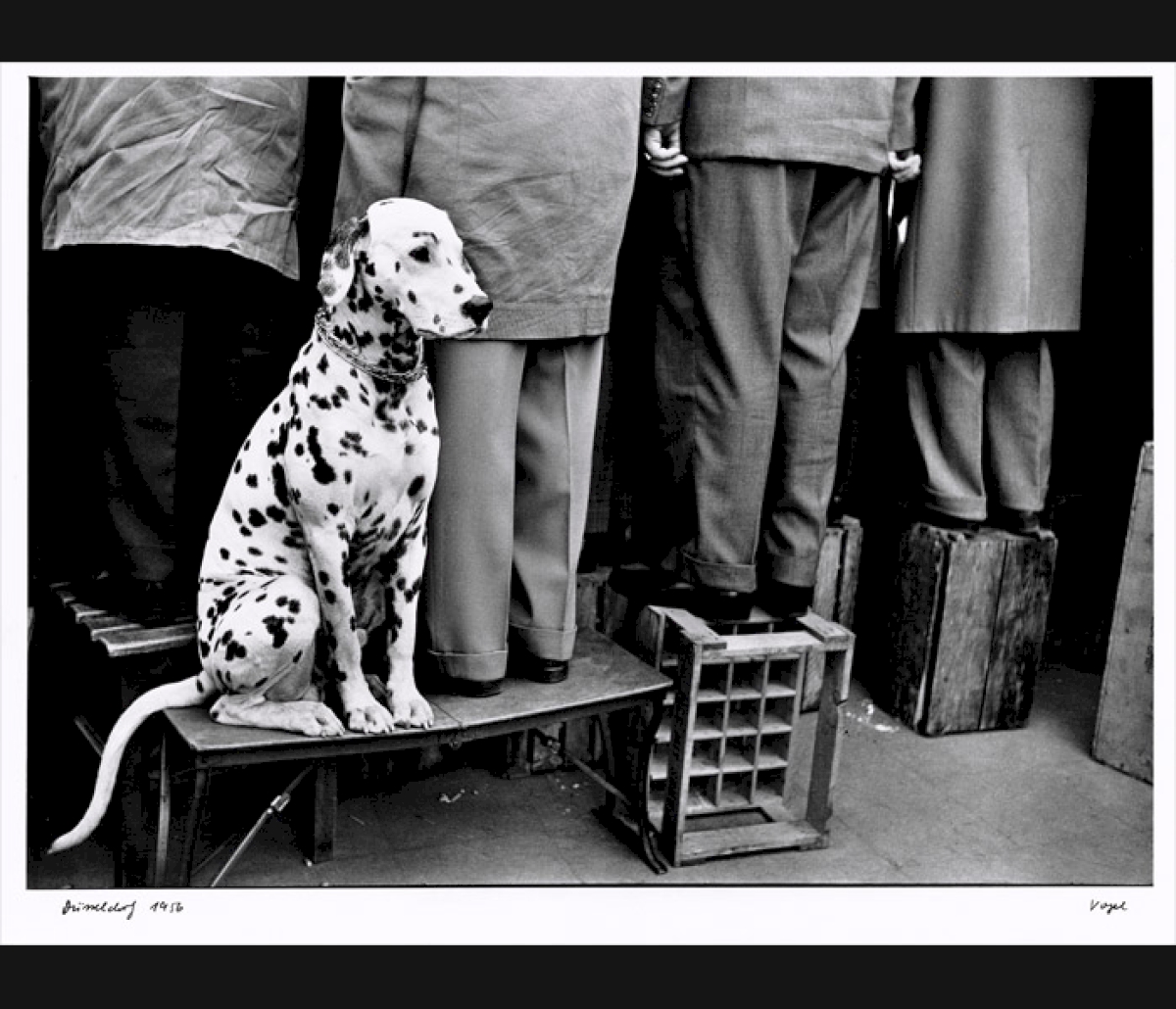

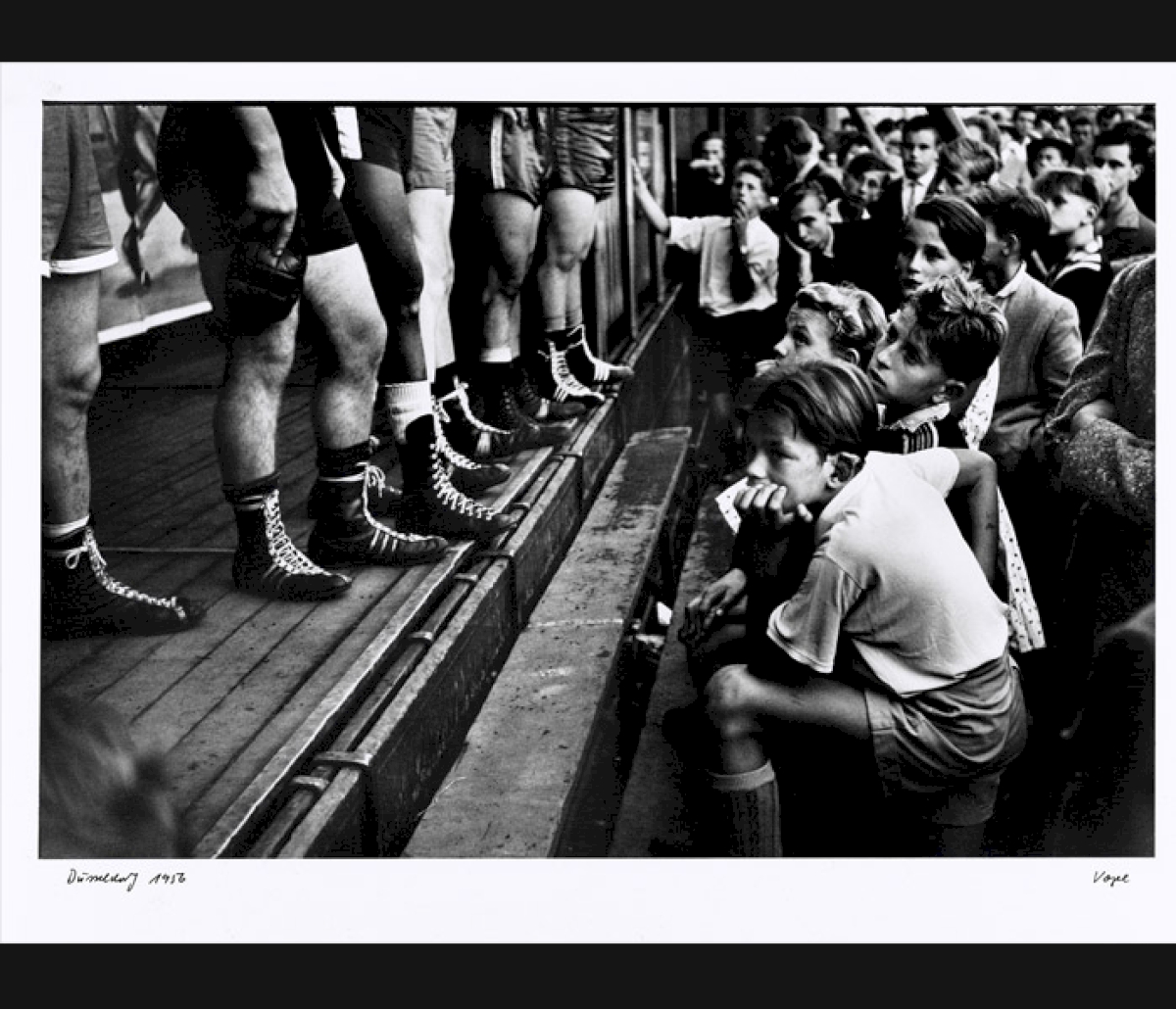

Just how can a small, black gadget produce such a superlative effect? Its pocket size, exchangeable lens, quiet operation, and fast shutter speeds made completely new fields of application, extreme angles, and spontaneity on an unheard-of scale became available to the photographer. Thanks to its use of standard cinema film, photography became a serial operation, affordable and available to everyone. The speed, freedom, and ease of operation it provided were a source of inspiration to photographers, and it met the needs of a dynamic age. Easily carried in one’s coat pocket, the camera sparked an enormous surge in photography, an immense sense of joy in experimentation, and an all-encompassing visual exploration of reality. The Leica thus set the standard for new horizons, speed, and aesthetic renewal, and it has retained its mythical status well into the digital age.

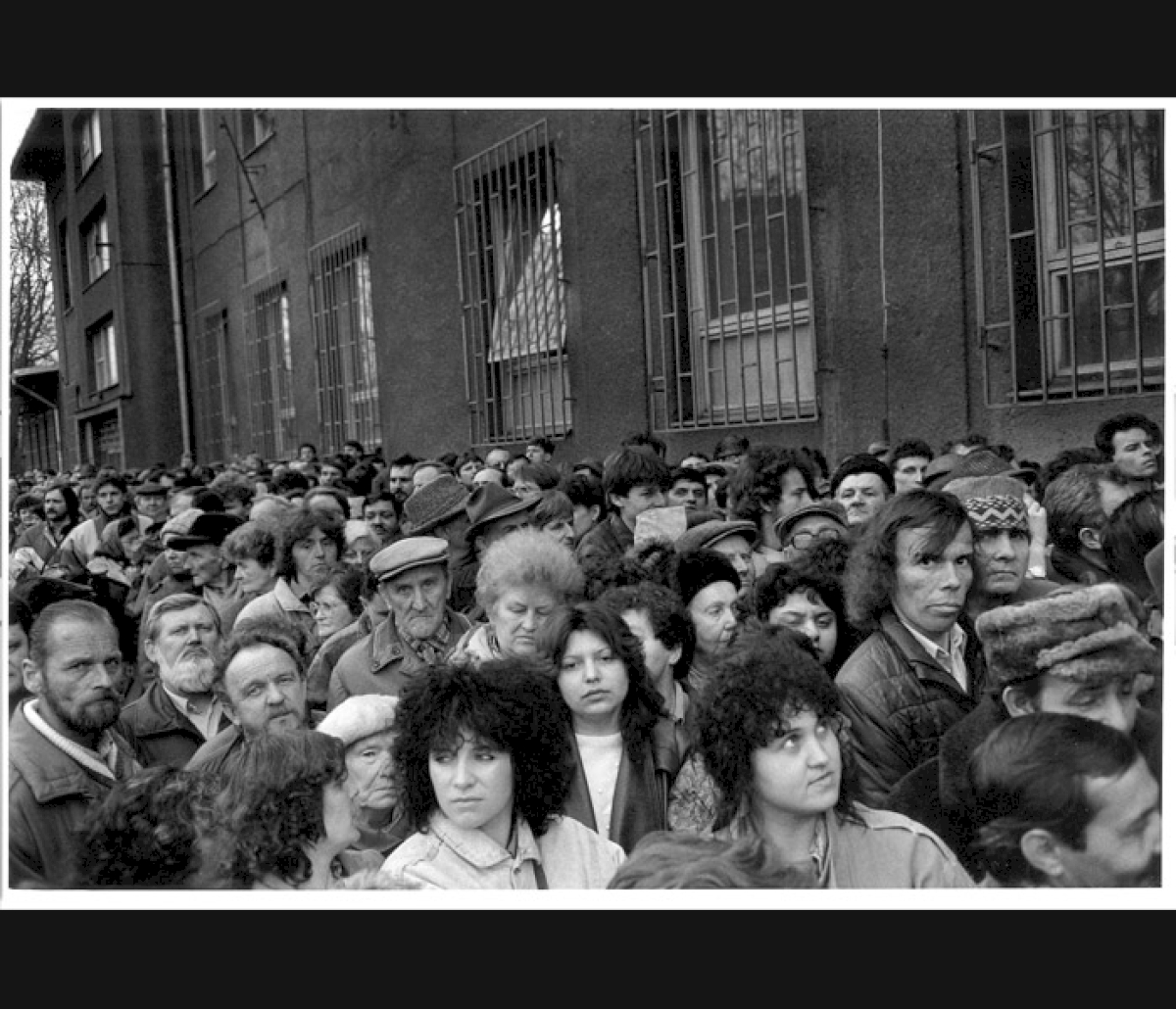

The exhibition “AUGEN AUF! 100 JAHRE LEICA FOTOGRAFIE” (EYES OPEN! 100 YEARS OF LEICA PHOTOGRAPHY) casts a light on many aspects of small-format photography. Divided into sixteen chapters, it ranges in scope from journalistic strategies to documentary approaches right through to unfettered artistic expression. Viewing photography from the perspective of art and cultural history for the first time, it illustrates how the Leica compact camera changed photographic vision in the 20th century. More than 300 photographs from international collections and museums as well as newspapers and significant photobooks document the various aspects of Leica photography from the mid-1920s on. The exhibition thus provides a stylistic history of the medium, running the gamut from the classic modern age to the post-modern diversity of the present day, from New Vision via “la photographie humaniste” to fashion photography, from “subjective photography” via author photography to street photography and contemporary art photography.

For this exhibition, Kunstfoyer Munich has brought together works by internationally renowned Leica photographers such as Alexander Rodchenko, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, Christer Strömholm, Bruce Davidson, F.C. Gundlach, Fred Herzog, Robert Lebeck, William Eggleston, Will McBride, Paolo Roversi, René Burri, Thomas Hoepker, Bruce Gilden, Mark Cohen, Nobuyoshi Araki, and many others.

The name Leica came about by combining the first letters of the words Leitz and camera. The original model was built by precision mechanic and amateur photographer Oskar Barnack in March 1914, and he immediately succeeded in capturing absorbing images on 35 mm cinema film. Barnack enlarged the size of the standard cinema negative to 24 x 36 mm, and in doing so, created a new standard frame size for 20th century small-format photography. It was not until after the First World War, however, that the head of the Wetzlar-based firm, Ernst Leitz II, decided to proceed with production, and the camera did not appear on the market until 1925.

The exhibition was curated by Hans-Michael Koetzle and has already met with great success in Hamburg, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, and Vienna. For its stopover at Kunstfoyer Munich, never-before-seen works by Hans Saebens, Werner Bischof, Paul Wolff, Gérard Castello-Lopes, and others have been added.