CLOSE ENOUGH

New Perspectives from 13 Women Photographers of Magnum.

"If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough." - Robert Capa

The Exhibition

Close Enough explores the practices of thirteen emerging and established women photographers of Magnum and the relationality they create within global situations, local communities, and interactions with individual subjects. Each contributing photographer openly narrates their creative journey, ranging from reflections upon long-term personal projects to work in progress and new pivots in their image-making practices. They give highly personal accounts of their visual vantage points and create a constellation of photographic relativity in this exhibition.

Set in the context of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the founding of the Magnum agency (1947), Close Enough focuses on women photographers whose distinct visions are currently shaping photographic perspectives within Magnum. Together, they move and challenge the photography collective’s boundaries, deepening Magnum’s anchoring of the photographic quest to take account of human experience and survival. In uniquely personal ways, the contributing photographers negotiate gaining access, holding their bearings, and moving deeper in relation to human subjects and experiences - the challenge to photographers to get “close enough” called forth by the cofounder of Magnum, Robert Capa. With determination, urgency, and resourcefulness, each photographer takes account of their practice, inviting us to get close enough.

Charlotte Cotton, Curator of the inaugural Close Enough exhibition at the International Center of Photography, New York, 2022

The Photographers

Alessandra Sanguinetti

Myriam Boulos

Sabiha Çimen

Olivia Arthur

Nanna Heitmann

Lúa Ribeira

Carolyn Drake

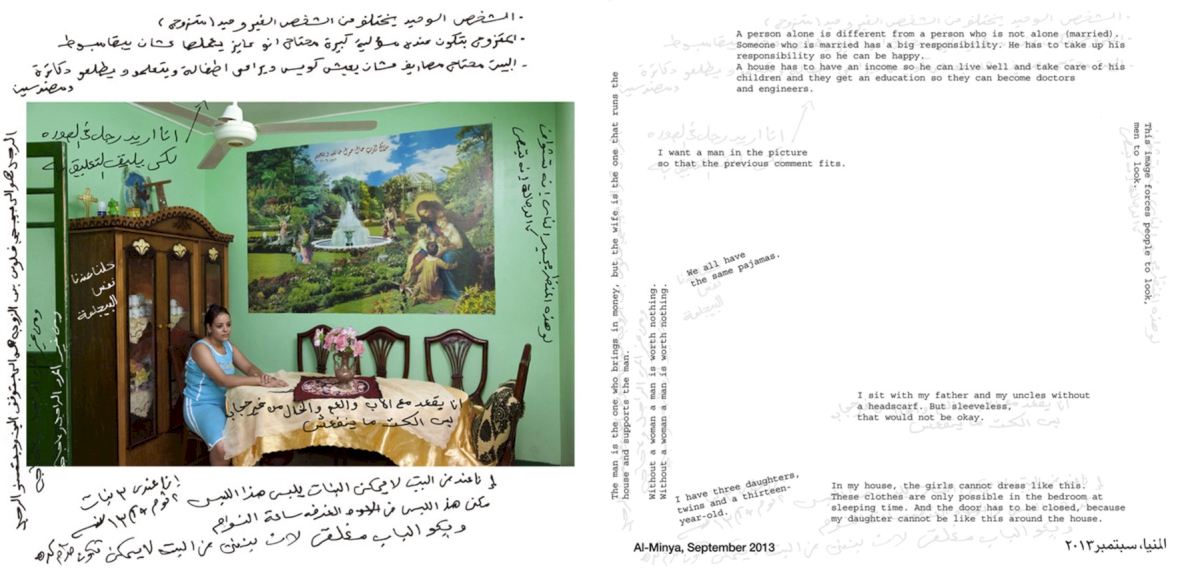

Bieke Depoorter

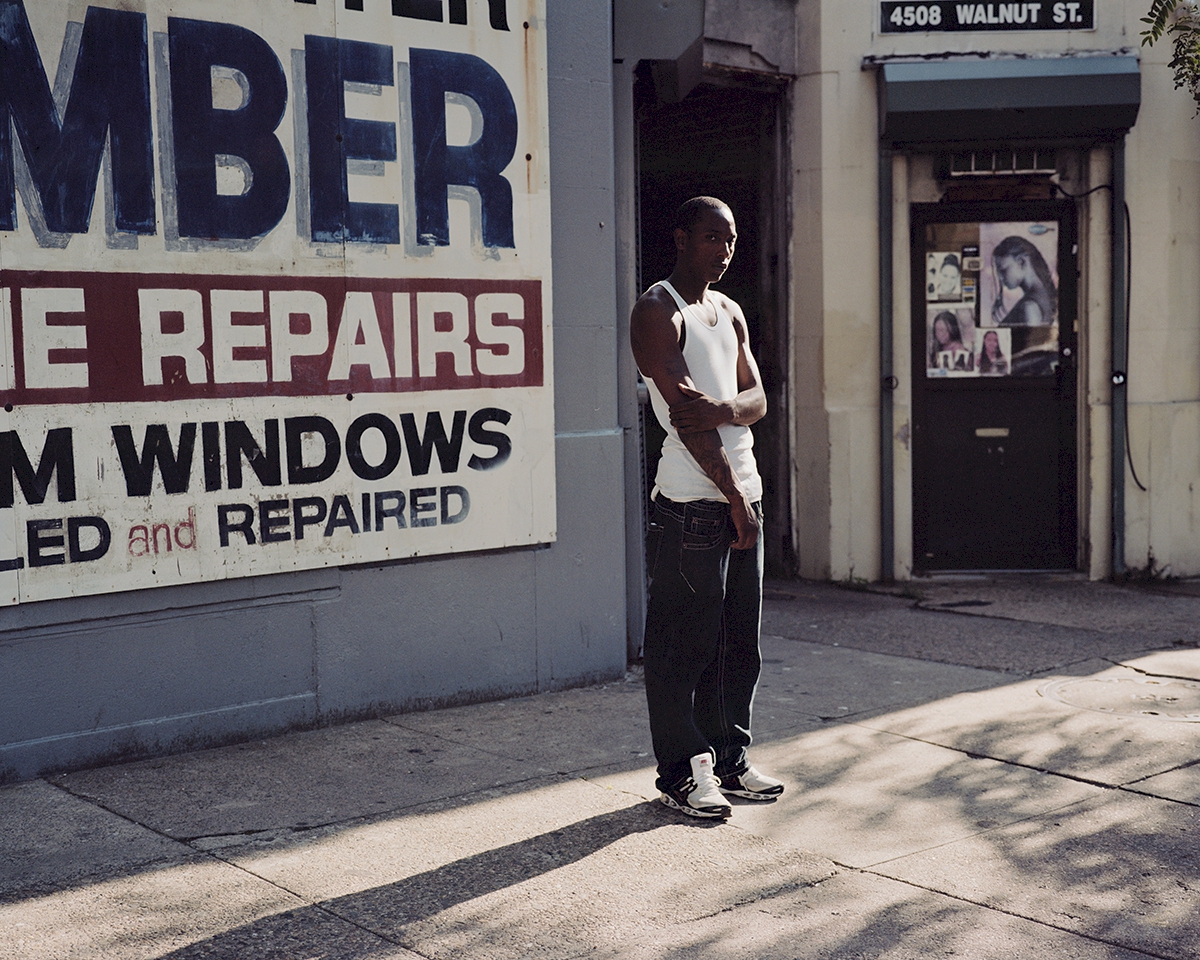

Hannah Price

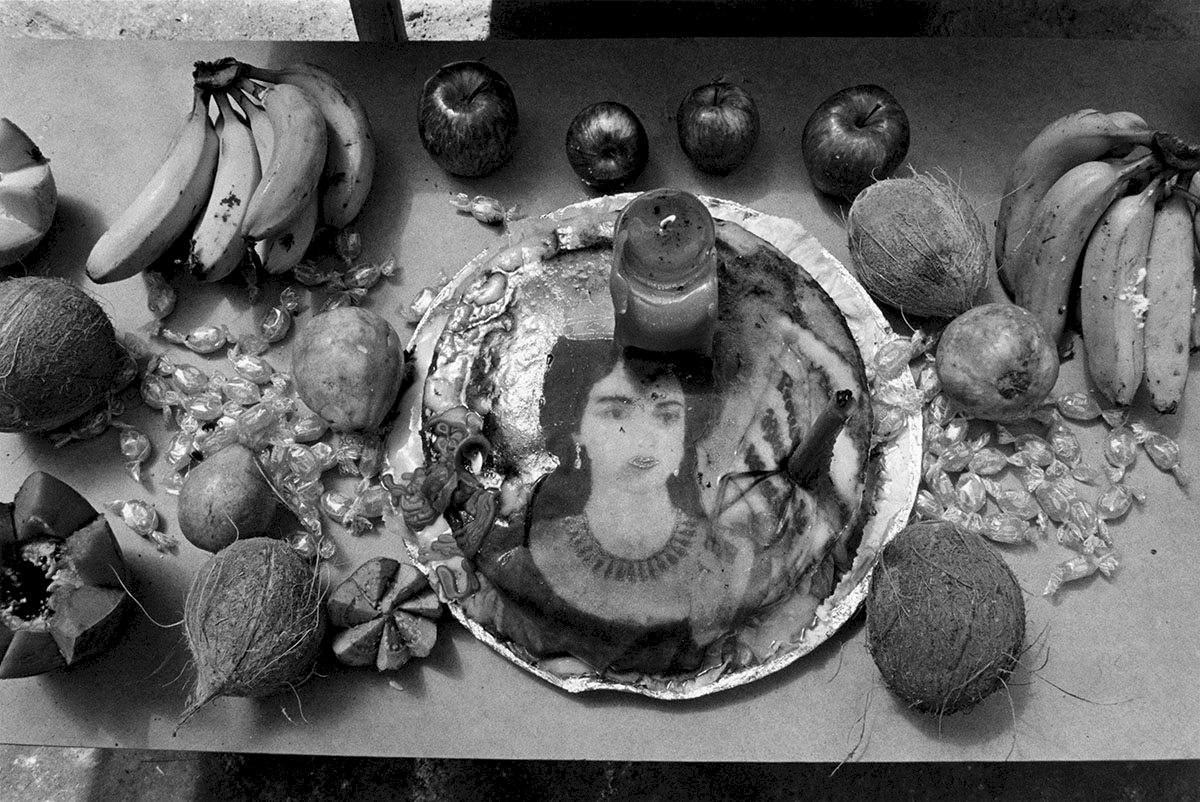

Cristina García Rodero

Cristina de Middel

Newsha Tavakolian

Susan Meiselas

The Views

Cristina de Middel

Decades ago, one of the founders of Magnum Photos supposedly pronounced a single statement that set a standard for the quality of an image and its documentary value. For the sake of history and its significance to future generations, the quotation is attributed to Robert Capa: “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.”

Early war photography often focused on landscapes, cityscapes, and the aftermath of battles rather than on the immediate and personal experiences of individuals. Photographers captured scenes of destruction, posed shots of soldiers in static positions, and staged compositions. Technological limitations, including long exposure times, made capturing action and movement challenging, and the results were far from the candid, in-the-moment scenes for which Capa became famous. Capa and Gerda Taro, the inventor of his alias, built his legend and planted a seed in the audience’s mind of the brave and engaged reporter stereotype that is still alive - capturing the truth as a way of life, whatever it takes.

Photography - as a vague, undefined, and almost newborn industry -struggled from the beginning to label itself as either craft or art. Such lapidary sentences were, and still are, greatly welcomed. How else would someone know if their images were good in an era when social media interaction was not there to quantify quality with likes? With no photography police, decalogues, or definitive manifestos to set the parameters, who or what is considered good or bad?

Many years went by and photography had to reinvent itself half a dozen times, but both Capa and his pronouncement remained relevant and reached a mythological status. Myths can offer psychological comfort and a sense of security. In the ever-changing photography industry, myths provide narratives that help photographers cope with its uncertainties and anxieties; believing in a larger sense of duty or destiny can bring solace and a certain control in the face of chaos. They basically give photographers a direction to start with, but like all myths, they need to be updated and reinterpreted. The industry and society seem to have finally understood this. Until quite recently, the world was explained to us from one angle, that of the white Western man.

For decades, the stories we consumed had a certain set of parameters and priorities that have since stopped resonating with a larger and more diverse audience. Prior to that paradigm shift, the myth surrounding the “close enough” idea was pushed to its limit and hyperrealistic images that ran at the speed of light were dumped in front of our retinas with no boundaries. War and conflict were exclusively served to us on a plate of raw meat for the sake of credibility, and any alteration to this approach was understood as a profanation of the sacred temple of documentary reporting. Media platforms have continuously provided more immediate and raw content to an avid audience that has 9 become incapable of processing the information and even more incapable of responding to it. Overwhelmed and paralyzed, the audience has just given up and dissociated.

I do not think it is a coincidence that the current loss of credibility that the media is facing and the rise in prominence of long-disenfranchised and sidelined voices is happening simultaneously. I am including, by the way, women as the largest existing group of this kind. Beyond the assumption that racial, geographical, and social classes that deviate from the “old norm” are now gaining their fair platform and are expanding the perspectives available, another question arises in my mind. Is there such a thing as a “female gaze”? Is it possible to say that there is something particular about how women, from all origins and backgrounds, perceive and explain the world? And most of all, is it possible to make that affirmation without falling into the good old stereotypes that define women only as gentle, generous, caring, empathetic?

When the idea for this exhibition emerged, this was one of the first questions that was raised and left unanswered because it is ultimately for the exhibition visitor and the reader of this catalog to decide. How could we state our own version of the story by imposing it on others, as one perspective had been imposed on us before? It is crucial to note that the photographers included in the exhibition and catalog do not always agree and sometimes have diametrically opposed understandings of certain realities. They each have faith in different things and use a completely unique set of tools and motivations in their practice that the work sitting next to it could question radically. There is no unity in this choir and no such thing as a sisterhood when it comes to work and entitlement, but please, let’s not see a problem in this opera formed only by sopranos. Eclecticism does not mean conflict in this new world. Maybe the lack of competition makes the whole thing more gentle and manageable. Who knows?

Like in a mountain range, the women in Magnum are peaks standing next to each other, each one with a name, each one with a story, each one with a voice. Maybe the thread that connects all the work included in Close Enough is the fact that none of us would ever pronounce a sentence that is meant to echo forever. We would all rather just keep on posing questions, to our audience and to ourselves. In Close Enough, you will find questions about the body, war, violence, sex, religion, racism, belonging, and aging. These are universal stories presented as universal questions in an act of combined assertive generosity and unapologetic humility.

Ultimately, Close Enough refers to a relative distance and perspective, one that is unique to each and every one of us, and one that turns the old “highway to truth” into a network of dust roads that take you to a richer and more layered version of reality. The journey itself is probably longer and more challenging, but the views …