Konrad Klapheck. Das Graphische Werk.

Konrad Klapheck? That’s the guy with the typewriters. This is probably what the Düsseldorf-born artist brings to most people’s minds. One of his best-known works is “Der Krieg” (“War”) from 1965, in which the painter depicts small handwheels mounted on black machines; marshaled as for war; they appear gigantic against a fiery red sky. In this fashion, he created a threatening war scenario – without depicting violent acts of war. Anyone who has set eyes on these and other machines by Konrad Klapheck will forever be under the sway of their suggestive power. Those who believe that cold-hearted technology cannot convey any messages or emotions are taught otherwise: the combination of realistic and surreal monuments to the machine and highly personal titles is Klapheck’s trademark.

But Klapheck has much more to offer: now, for the first time, his graphics are the focus of an exhibition. It illuminates the evolution of various motifs and the intricacies of the printing techniques involved; it reveals an exacting craftsman and intellectual who fathoms the fine subtleties of commentary and humor. The exhibition is also a birthday present marking Konrad Klapheck’s 80th birthday on 10 February 2015. 120 works and the catalogue raisonné of his prints compiled by Deutscher Kunstverlag are on display in honor of the artist.

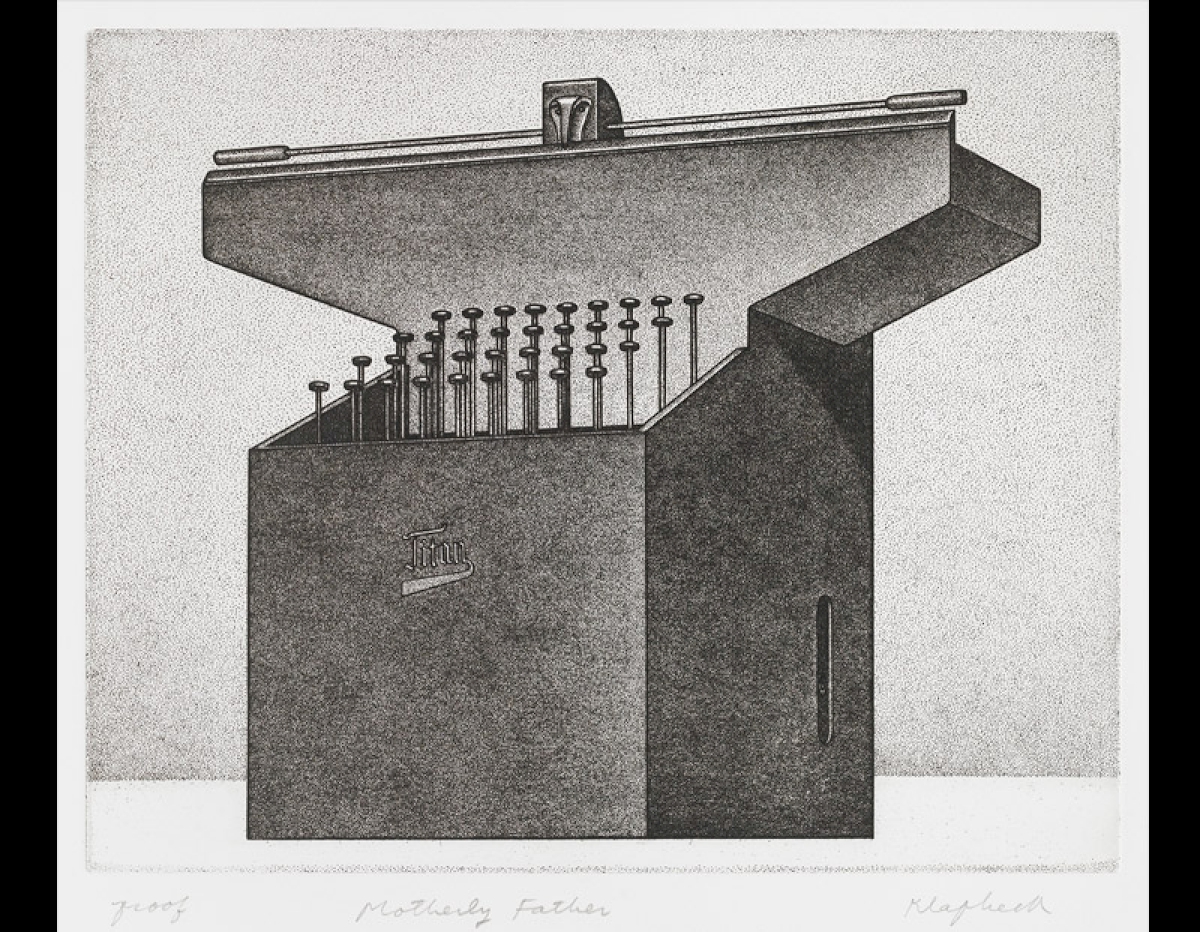

It may seem belated that this treasure trove of graphic works is only now being spotlighted, but one must bear in mind that when the first retrospectives were held in the 60s and 70s, Klapheck had only completed four lithographs and four etchings. He did not explicitly explore the possibilities inherent in the technique of etching until 1976/77, during which time he produced 20 works. The exhibition encompasses a total of 120 lithographs and etchings dating from 1960 – 2007: from his early graphics, the beginnings of his interpretive depictions of the world of objects, to the human figure – an entirely new theme that found its way into his world of images during the 90s. The various proofs, variations, and color variants not only provide a glimpse into the struggle for motif and composition with regard to his oil paintings and the interaction between the two genres, they also bear witness to Klapheck’s aesthetic understanding as artworks in their own right. Klapheck himself states that graphics relate to painting in the same way that a piano reduction relates to an orchestral score. “There is much that cannot be conveyed in a piano reduction; it can neither convey the acoustic color of the instruments nor the timbre or variations of vocal expression. But what does become clearly visible and audible are the structures of a composition.” And, one would like to add, Klapheck’s way of thinking.

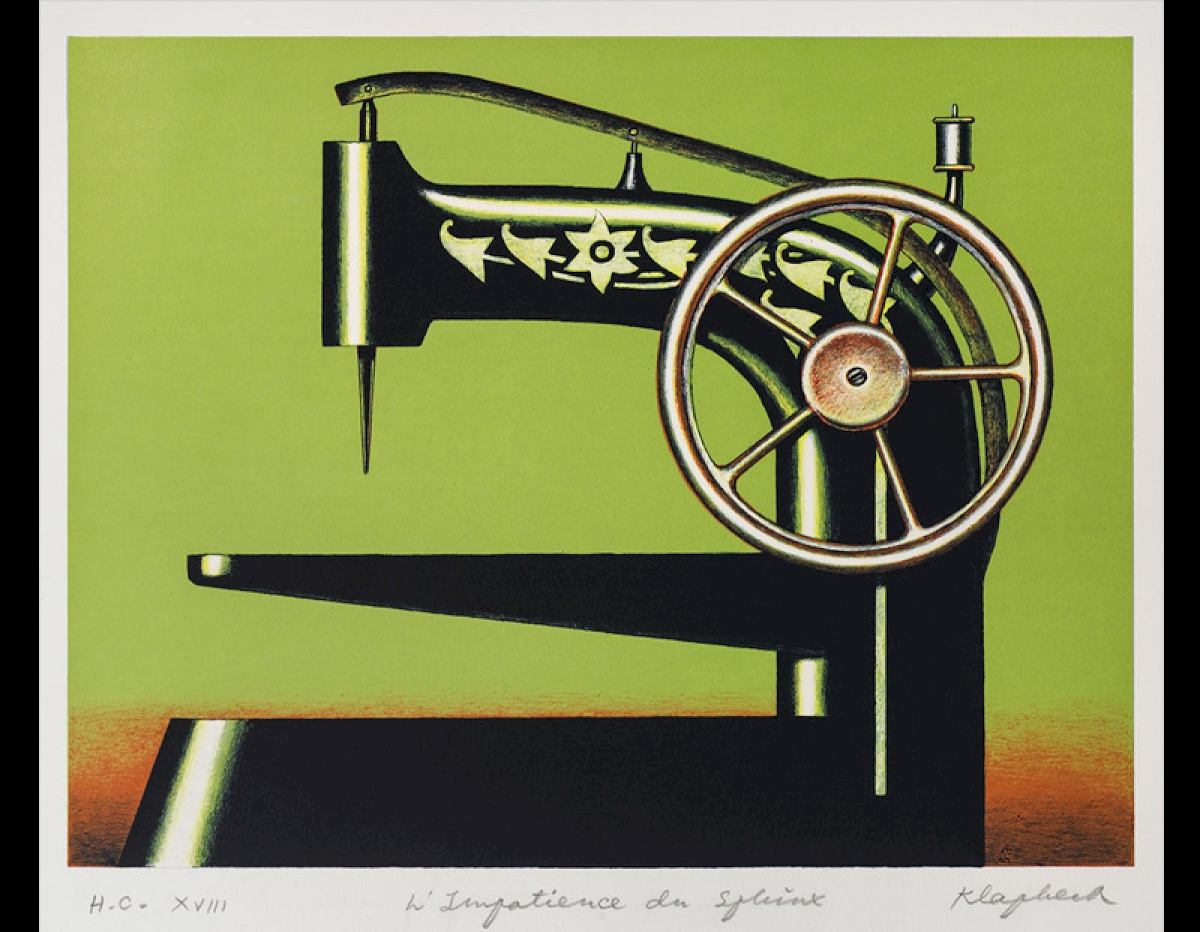

Klapheck’s world is anthropomorphous. In it, he elevates technical and industrial devices to monuments of our society. When a drill bearing a floral design is titled “The Intellectual,” a delicate etching with a hint of color done in 1964, then spirit is bestowed upon objects – and upon our work environment. Similarly capricious is the sewing machine dating from 1998: with its arrow-straight needle mounted on a slender arm and rendered in contrasting blacks and greens, it is transformed into the “The Impatience of the Sphinx.” In the exhibition catalog, writer and curator Siegfried Gohr describes the fascination and paradoxes of Klapheck’s works thus: “Everyone who views his works senses the tension that arises from them because precision and the enigmatic are both at work, and they convey the peculiar experience that everything and nothing is self-evident.”

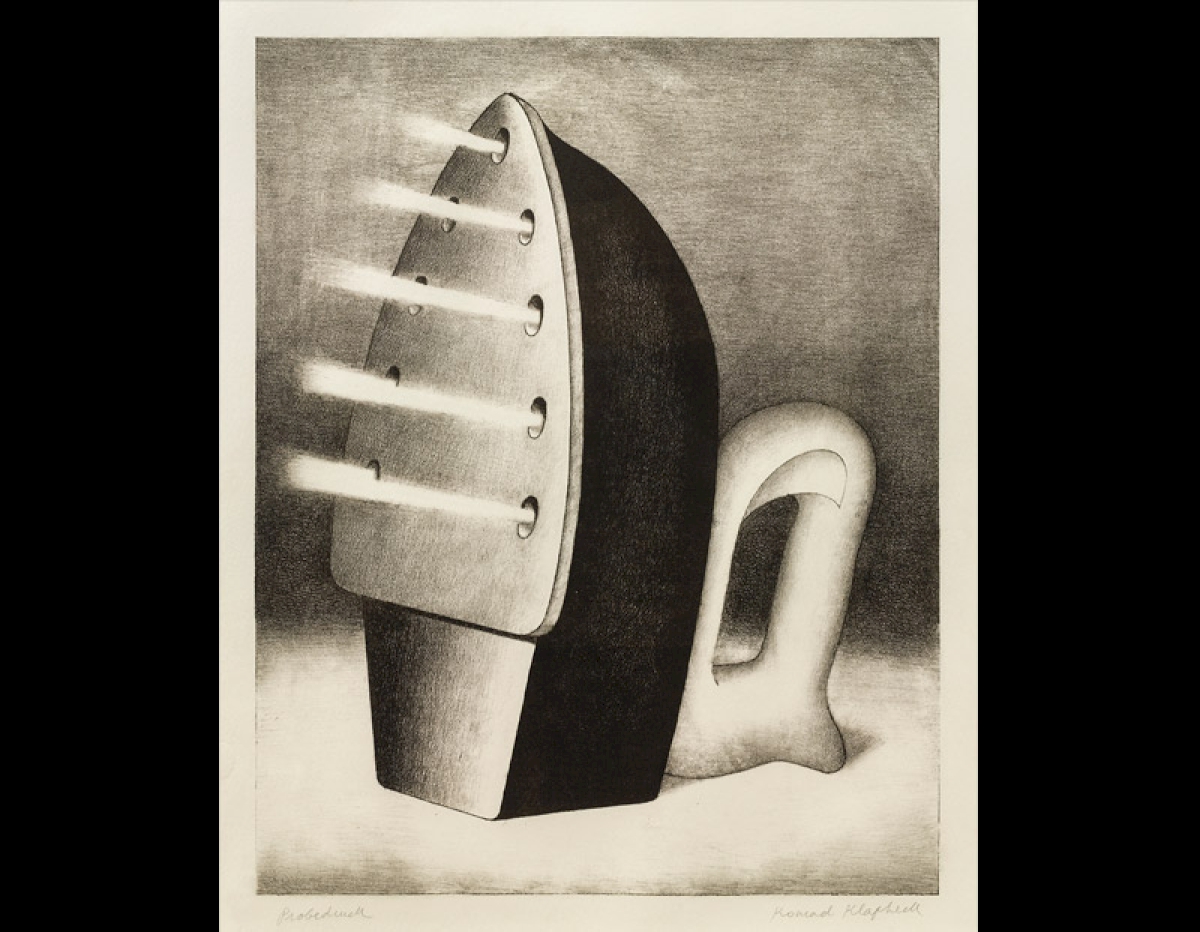

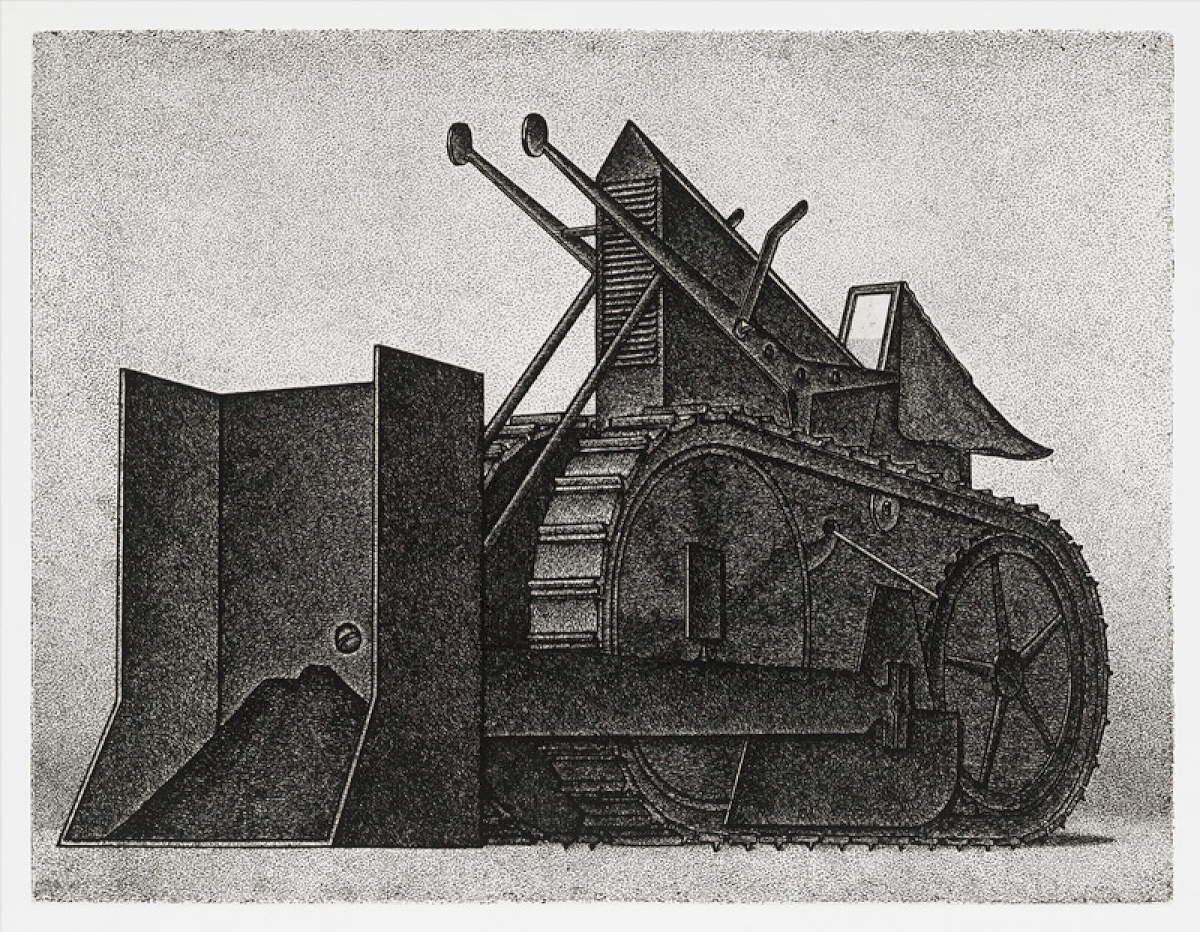

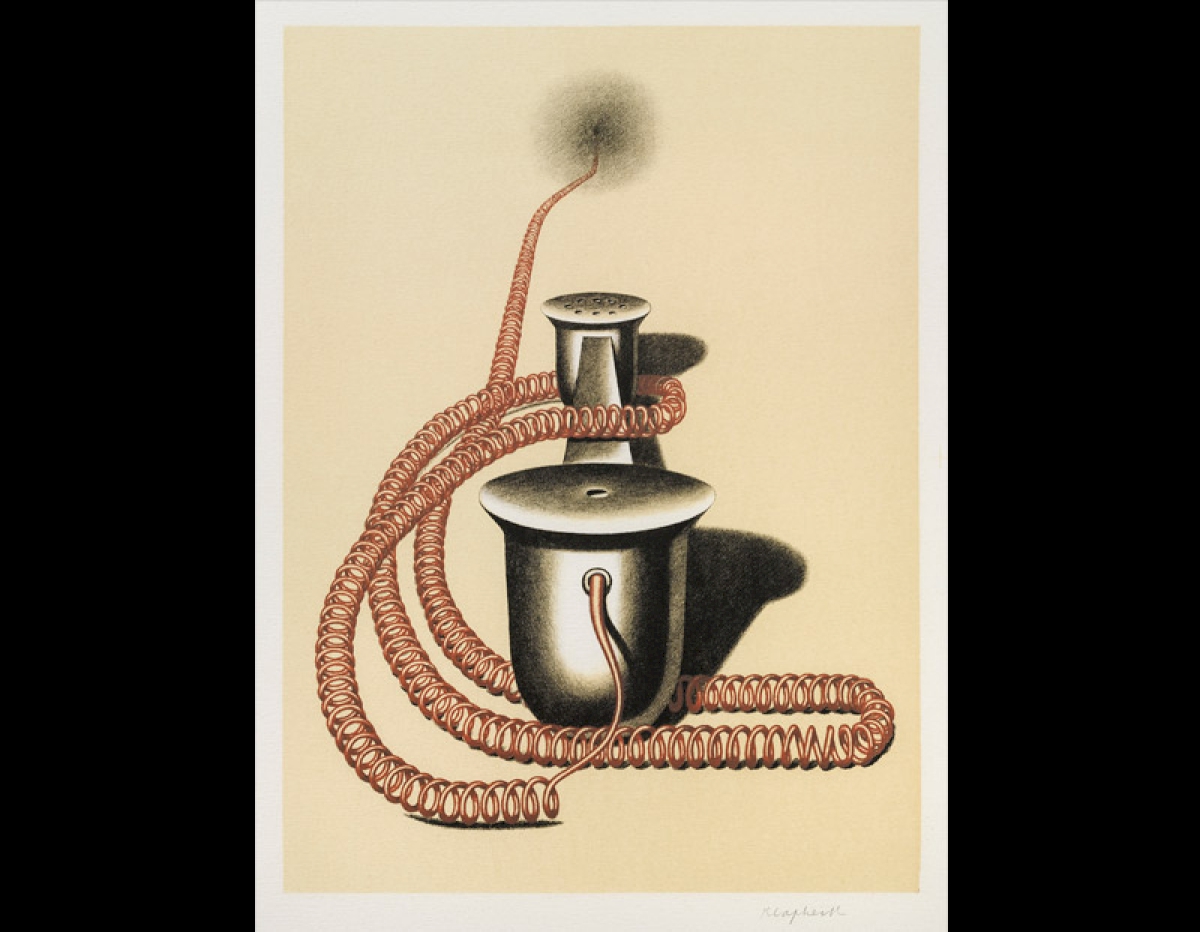

Konrad Klapheck participated in numerous documenta exhibitions and held a professorship at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf for several decades (from 1979 until 2002). Quite early on, he began taking an interest in the enigmatic and surreal and was undoubtedly influenced by Dadaism, which upturned the significance of things and, above all, their valuation. Klapheck displaces reality by means of unusual perspectives, asymmetry, vertical exaggeration, and hyperrealism. He enhances the impact through enlargement, isolation, and duplication, and is thus in close proximity to Pop Art with its social criticism and anti-consumerism. The quiet irony that marks his work is also unique: a track and field shoe lying on its side from 1967/68 is titled “Die Pleite” (“The Flop”); “Die Fragwürdigkeit des Ruhms” (“The Dubiousness of Fame”) from 1980 depicts a bicycle. “Die Schwiegermutter” (The Mother-in-Law”), a steaming clothes iron from1967/68, is also well-known and was refined by Klapheck in numerous variations. He made a harem out of shoe stretchers (1967/68) and transformed a captivatingly symmetrical zipper into a “Schürzenjäger” (“Womanizer”) in 1976.

Klapheck reveals the profusion of associations a seemingly neutral world of everyday objects can offer. Typewriters are associated with the “Triumph der Erinnerung” (“Triumph of Recall”) or with a “Meisterdenker” (Master Thinker”). “Der Gesetzgeber” (“The Lawmaker”) turns out to be a large keyboard or adding machine. A bulldozer represents “Glanz und Elend der Reformen” (“Splendor and Misery of the Reforms”) in 1976/77, and a telephone serves as “Der Statthalter” (The Deputy”) in 1975. The meticulousness of the graphics is given a twist by their subversive titles, and one often discovers autobiographical aspects. As the key rack from 1976/77 reveals, “Schicksale” (“Destinies”) are the underlying cause of everything.

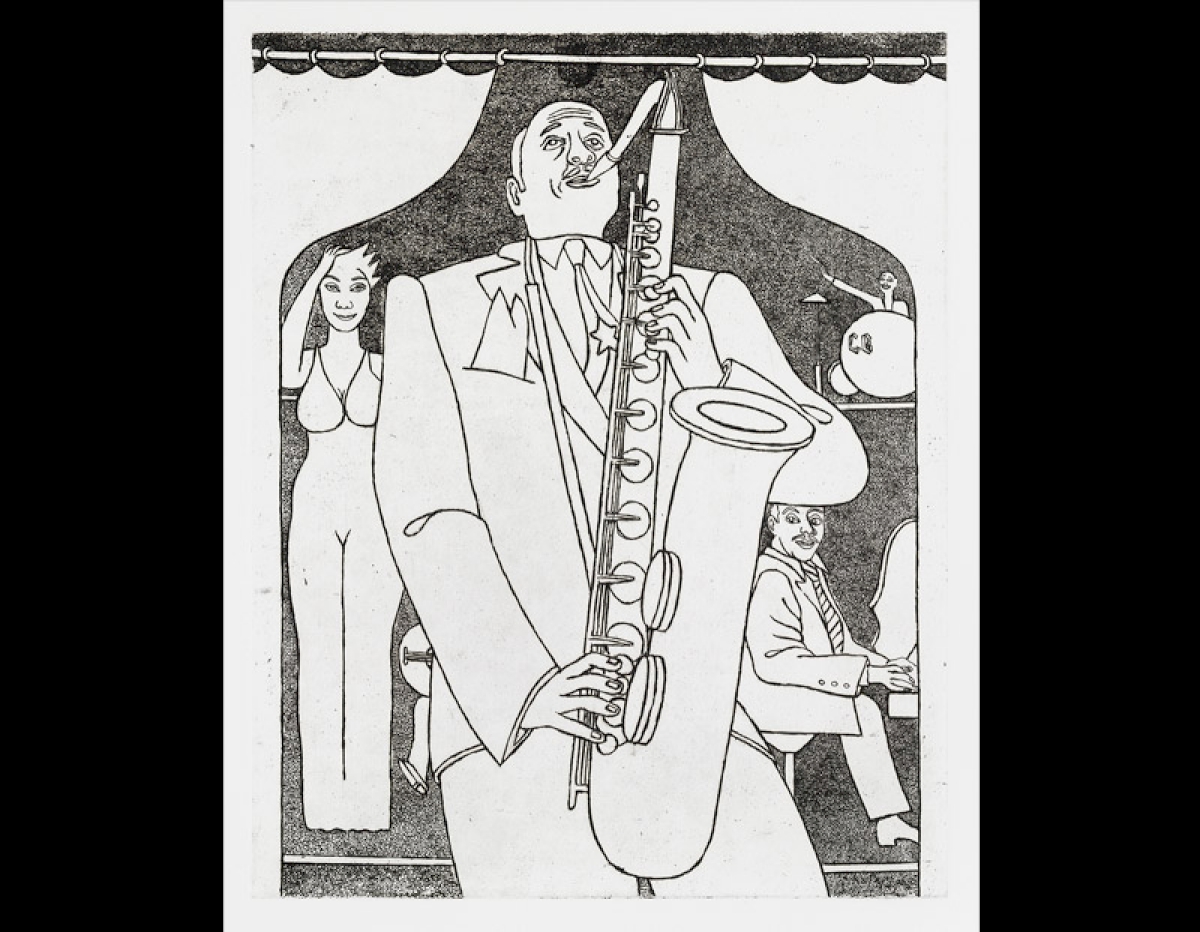

It therefore comes as no surprise that Klapheck bade farewell to his accustomed repertoire during the 90s and henceforth devoted himself to drawing the nudes and jazz musicians that had fascinated him since his youth. Here, too, he mixes together a well-nigh classicistic style and extremely precise contour lines with an entirely unique spatial experience. Whether dealing with personal memories, demons of the age, or icons of technology, in the final analysis, Klapheck employs variation in order to expand the scope of perceptional possibilities. Die exhibition was curated by Siegfried Gohr.